How to measure engagement and choice of your learner?

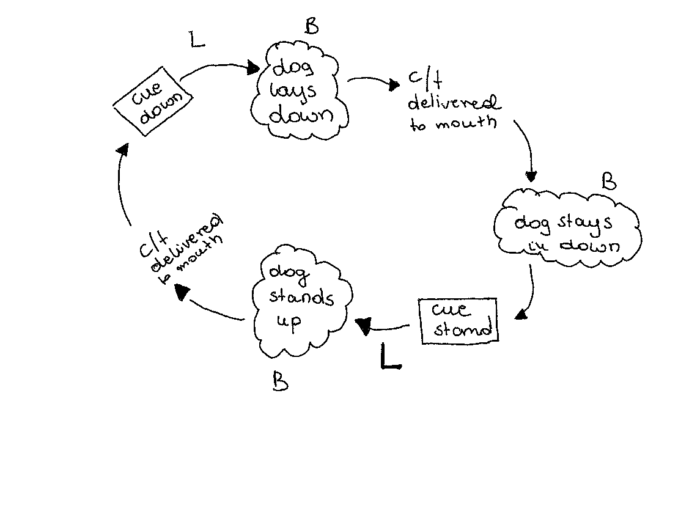

“If you don’t graph you are not doing ABA” I first heard this quote during my ABA program at Florida Institute of Technology. Taking data is crucial if you want your training to be effective, fluent and efficient but what may come as surprise, also if you want your learner to choose to fully engage in the learning process with what we may call “discretionary effort”. There are multiple measurements we can take to analyze behavior. I want to focus on latency and why I consider it one of the most helpful assessment tools of “learner’s engagement and choice” during training session. LATENCY, or response time. Latency refers to the amount of time that elapses between the onset of a specific cue or stimulus and the response of interest. We want this phase to be as short as possible; it reflects the understanding of a cue, the skills needed to do a behavior, the engagement and reinforcement history of a given cue. A slow response may also indicate that the environment and competing stimuli are too strong in relation to our cue reinforcement history.

What is choice? What is engagement? Both these are labels. Labels that we can define by operationalizing crucial components. I do that thoroughly in my course Let Me Want It. For this article let’s consider choice to be a contingency where learner has access to variety of reinforcers available for multiple behaviors, and has skills to engage in those behaviors. In case of a training scenario this can be described as your dog getting cookies for interacting with you, or getting cookies, walk, toy for opting out or performing other, different behavior: sniffing, looking away etc. When I say my dog chooses to work with me, what I mean by that is, dog performs start button behavior that begins training session in a situation when reinforcement is available for other activities. Antecedent arrangement signals him availability of reinforcement for both training and/or other behavior. Engagement on the other hand, is what I would call “discretionary effort” in performing behavior. Sounds labelish, doesn’t it? Yes, we need to operationalize it better. Discretionary effort is the level of effort one could give if they wanted to, but above and beyond the minimum required. For me this is a dog who:

- Responds to cues with no latency

- Moves as fast as possible (according to criteria for specific behavior)

- Stays in a focus bubble appropriate for particular activity (does not interact with the environment and other competing stimuli)

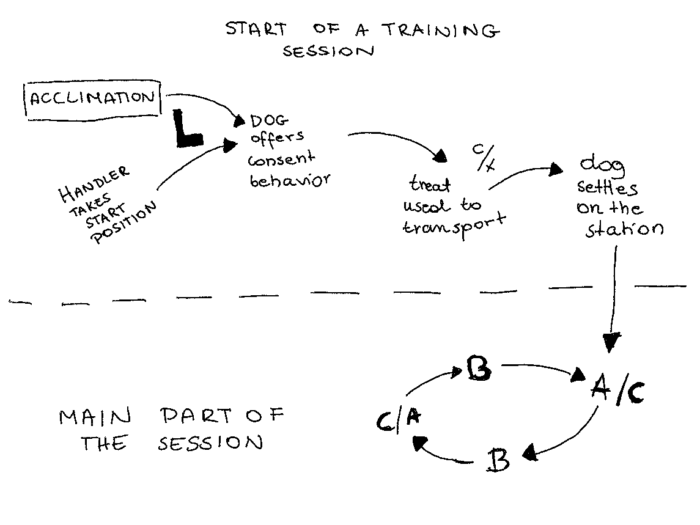

My goal during the session is to have every minute of it meaningful. There is always something valuable happening. Either my dog is on the mat, being transported, performing behavior, eating food or playing toy (btw Eva and Emelie have a great course on just this topic – check out Seamlessness). We can look into each and every one of these, take data to assess whether or not we have our learner still on board. 1. Start of the training session: Time that passes between cue and behavior. Measure it, take data. Establish baseline to know how much time it usually takes for your dog to say yes.

- Is this not an offered behavior? Start of the training session?

In my training scenario, I don’t call my dog to start training. I offer him time to look around the environment, get used to it and then I give a cue by standing still, in a formal position. Now it is up to my dog to offer “star button”, “consent”, “choice” behavior” that is: jump on me, offer hand touch, stand still in front (or whatever the behavior has been taught in these conditions.) I don’t prompt it in any other way. Like with all “offered behaviors” there is always a cue somewhere in the environment. But there is no additional cue present. Usually the ending of C – our treat, toy delivery, signals the opportunity to earn reinforcement for another repletion of the same behavior. In my case, the cue is definitely in the environment, context. But according to my criteria I would still call it offered behavior. What can I actually measure and what will it tell me:

- time it takes to offer start button, consent behavior. I want to have baseline. I want to have clear data how much time my learner needs in environment (it will vary in different environments). Thanks to this I won’t be waiting 30 minutes for my dog to say yes, if his baseline is 2 minutes. This helps me to accept more silent no. I don’t need to wait that long, because the average time tells me if my dog is ready or not.

It will also give me information about the difficulty of the environment. If at home, my dog offers consent behavior within 2 minutes and I have now moved to new location, and the time increased to 20 minutes, it is a good feedback that this location may be too challenging, and I should search for the easier place, where this time will be closer to the one I had at home. Look at this video, can you see how fast Gapcio starts jumping on me – his consent behavior, how quickly he says yes. Latency is practically 0 in this video. https://www.facebook.com/AgnieszkaJanarekAnimal/videos/1877460999038772 Now take a look at this one, it is a video recorded over 5 years ago. Look how much more time it takes him to say yes. If the above video shows the baseline, then what can we say about this one:

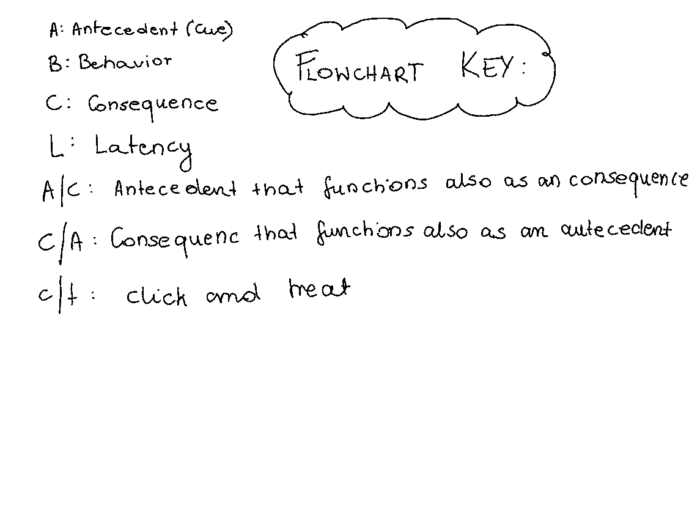

For me this video shows a NO response. No in given in latency to cue. 2. Time between delivery of food, toy and another repetition or readiness for that repetition (standing in default position to hear the cue), throughout the session. In other words time between C and A or B (C functioning as an A in offered behavior loop). Technically we can say that treat taken, eaten functions as a cue, which means we can call that time between delivery and another repetition latency. If we look at this setup: tossed treat, dog follows it, eats it, returns and stands in front of handler offering eye contact, click and loop repeats itself. Assessing time my learner needs to offer another repetition can indicate if I still have yes to continue, how engaged is my learner in what we do, how difficult is the environment (does it catch his attention in a way that gets him out of focus bubble?). It can also tell us our errors in mechanics or choice of reinforcer or delivery pattern, – look at the video: 0:38 I have tossed the treat the way it was confusing for Gunia, look how much time she needed to come back to me. But this is a topic for another article.

A great example of “NO” said by Gunia during our husbandry training. We were doing preparation for blood draw and use of veterinary tourniquet and she waited beautifully until the click, but she said no to the next rep. I assessed that based on latency. I know how fast she usually offers this behavior. This was way longer than usual. Probably if I have waited longer she would have said “yes”, but would it be truly yes? Or more likely, there is no other choice “yes” ? I really enjoy those small discussions we have during training session. I learn to listen, without her having to shout at me. https://www.facebook.com/AgnieszkaJanarekAnimal/videos/915372215322927/

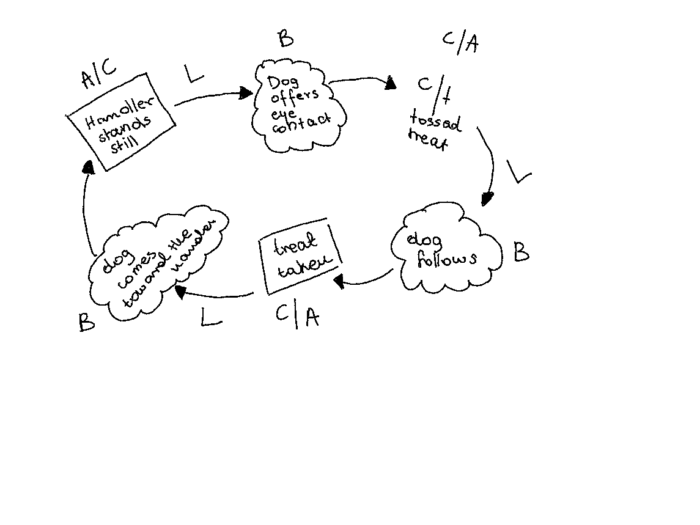

3. Actual latency for the cue. Time your dog responds to cue can be assessed through choice prism. One way to look at it is to consider the difference between OC and CC , but also we can look at latency for cues whether or not our dog is still saying YES, throughout the training. Training is a dialogue, since our learners have no ability to use verbal language to communicate with us, we have to listen by observing their behavior. Latency is one of the coolest tool to use to do that. If latency for the cue increases and instead of immediate response to heel cue your dog needs 4 or 5 seconds – it is a red light telling you that there is no longer yes from your learner. This applies to both visual and verbal cues. If you offer hand for chin rest and your dog doesn’t respond immediately, you keeping that hand is like repeating a verbal cue over and over again. Look at this example, I was backchaining position changes. The first sequence was done at the beginning of the session. Look at the latency for stand cue. Now compare it to the second sequence on this video. It was done after 6 reps in between. Latency increased A LOT. I can assume my learner is no longer engaged in the training session and it is a feedback for me to finish this exercises here, because there is a great chance next repetition won’t be even as good as the last one.

One more note about offered behaviors and use of rate as measurement: What happens with offered behavior. When there is no particular cue that we can distinguish. I asked about this Eva Bertilsson and she said I should check Skinner Box experiments to see how they have measured latency. But the thing is, what they have focused mostly with free operants (behaviors that have discrete beginning and ending points, require minimal displacement of the organism in time and space, can be emitted at nearly any time, do not require much time for completion, and can be emitted over a wide range of response rates. Skinner used rate of response of free operants as the primary dependent variable. He focused on observing the rate with which a rat would press a bar to get food.¹ Rate has its place in our data collection, but if we compare the information we can get from both latency and rate, we clearly see that latency gives us better overview of what we call “discretionary effort, choice, engagement”

- Session 1 (5 minutes)

10 reps of set-ups to heel, each has latency below 1 second.

- Session 2 (5 minutes)

10 reps of set-ups to heel, latency was below 1 in only 5 first reps. Then it increased to 5 seconds.

Each session has the same rate. Difference was in latency. Session time was the same due to other factors (speed of treat, toy delivery). Which one would you tell was more successful session?

Conclusion:

There are multiple other ways to measure behavior. I am not saying latency is the only one we should look into, but I do think it gives us a very good feedback that we can use, to improve not only effectiveness, efficiency, fluency, but also engagement of our learner throughout the training session.

¹ Human Motivation, David C. McClelland

See also other posts:

June 30, 2023

Get Your Lost Dog Back Home Quickly: Follow These 12 Tips for Success

Vacations favor more frequent and longer walks with our furry friends. We travel, visit new places. Summer makes us loosen our brakes and allow our…

June 30, 2023

Managing Aggressive Dog Behavior: Tips for Peaceful Living

Living with an aggressive dog may seem challenging, but it can be peaceful and manageable with the right approach. One key aspect is to remain…

June 30, 2023

Unlocking the Secret to Successful Puppy Socialization: Quality over Quantity

Today, although the topic is very important, I will keep it brief. Socialization is a topic that could fill books or scientific papers. However, today…